» October is American Archives Month: Charleston’s Hospital Workers Strike by Mateo Mérida

This blog post is written by Mateo Mérida, who is a graduate student for the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture during the 2021-2022 academic year. Mérida is a student in the College of Charleston's History Department.

In the grand scheme of American history, the year 1969 stands out as one of the most impactful of all. It marked the first human beings to land on the moon, one of the most culturally significant music festivals to ever take place in Woodstock, and a slew of protests surrounding the Vietnam War throughout the year. In Charleston, 1969 holds a particularly unique place in the city’s memory, as a union of Black hospital workers led the city’s most significant protest of the civil rights era.

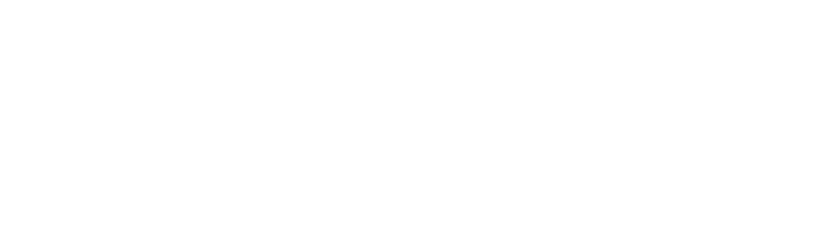

Much of this story centered around one of these hospital workers named Mary Moultrie who recalls many of her memories of the strike in an oral history interview with Jean-Claude Bouffard. Like many other assistant nurses, Moultrie was a Black woman, who worked at the Medical College of South Carolina, for $1.30 an hour, which translates to $9.69 today. In addition to being underpaid, these nurses regularly found themselves overworked, and constantly in fear of losing their jobs for minor infractions. In response, Moultrie founded a union of her fellow nurses, and agreed to meet with William McCord (the school’s president) to advocate for the changes they wished to see. Moultrie and the eleven other nurses met with McCord were fired on the spot. In response, Moultrie and the union launched a strike which lasted for 113 days.

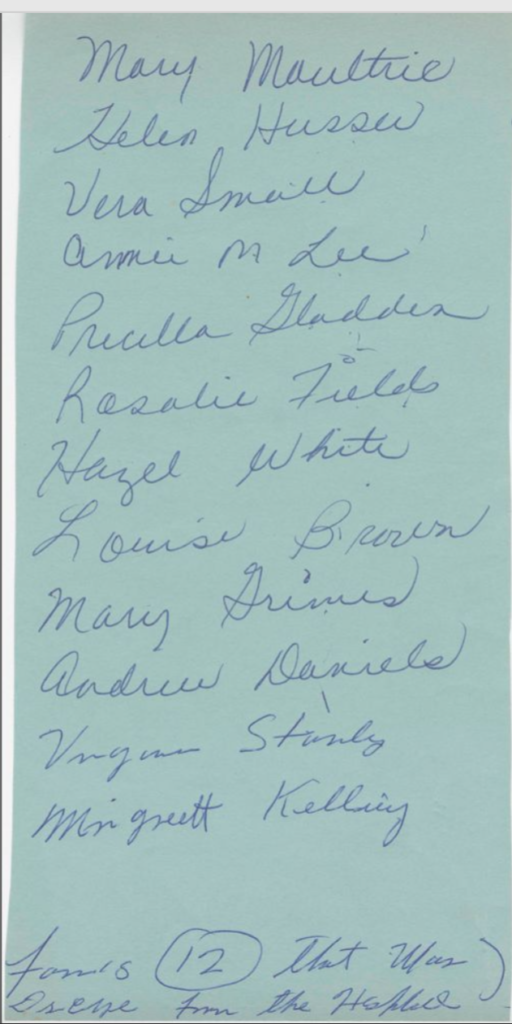

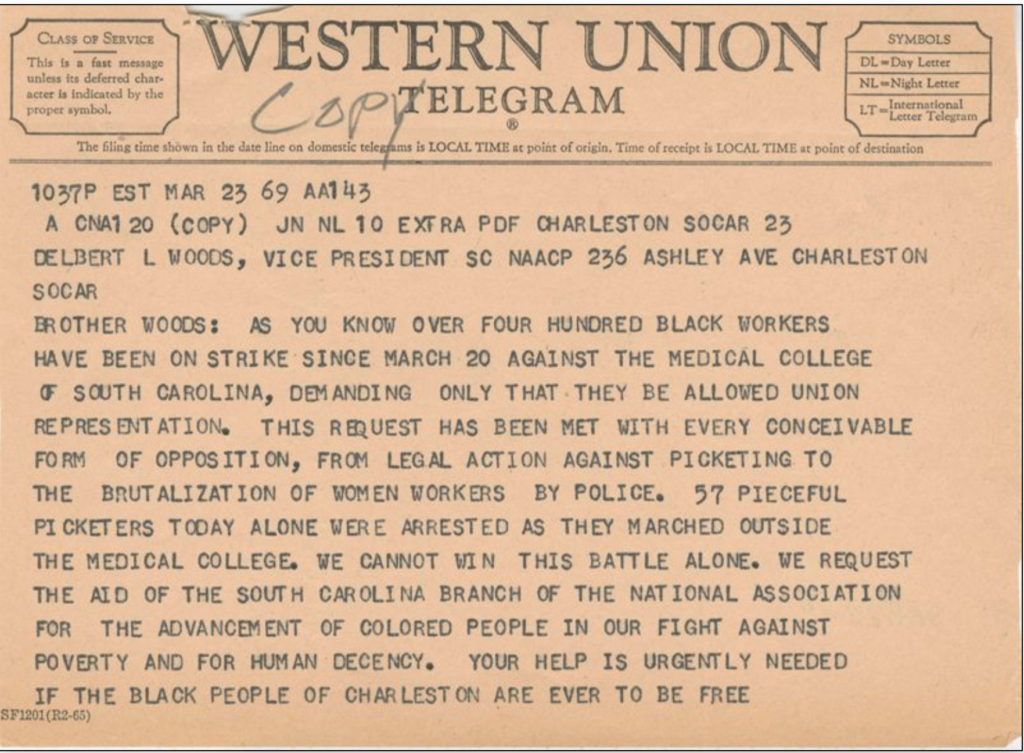

In many ways, the nurse’s strike in Charleston embodied much of what characterizes the civil rights movement across the U.S. Of course, the racial implications were clear to everyone, as Moultrie recalls in her interview that many white Charlestonians were fearful of advocating for the hospital workers, and Black Charlestonians—men and women—saw ample harassment from police for their protest, despite it being a peaceful one. There were efforts made to involve the National Association for the Advancement of Colored people (NAACP), as this telegram from Charleston activist Isaiah Bennet shows. Similarly, while Martin Luther King, Jr. had been assassinated nearly a year before the start of the protest, his legacy was fully present with the involvement of Robert Abernathy (president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference after King’s death) and Coretta Scott King, both of whom supported the local movement. Moultrie and the strikers also held a memorial service both in a church and in front of the hospital to commemorate Martin Luther King, Jr. one year after his assassination.

The strike led to a boycott, which helped to apply economic pressure to the city of Charleston, in an attempt to force McCord to bring the strike as a whole to an end.

When it did finally end, all 12 nurses, including Moultrie, got their jobs back, and were promised fair payment for their labor, equal to that of the white nurses. Similarly, the strike also helped to elevate the entirety of the Charleston Black community. As historian Leon Fink describes in the journal Southern Changes, it helped lay the foundation for more Black Charlestonians in state government. Yet, perhaps the most notable changes for Moultrie took place in her actual place of work, as white nurses began to demonstrate more respect for their Black coworkers. She describes “I mean at one point even in the cafeteria, the blacks and whites didn’t sit down and had [sic] lunch together, even if they worked in the same unit. When we got back to work that was different. If black and white staff was working together, and you were scheduled for work at the same time, then you’d go down and sit and eat together and talk.”

To learn more about the Hospital Strike of 1969, check out the Avery Research Center’s archival collections related to Isaiah Bennet, William (“Bill”) B. Saunders, and Septima P. Clark for more information.

Work Cited

Fink, Leon. “Union Power, Soul Power: The Story of 1199B and Labor’s Search for a Southern Strategy“. Southern Changes: The Journal of Southern Regional Council, 1978-2003. Vol. 5, 2. 1983. pp. 9-20.

Moultrie, Mary. Interview by Jean-Claude Bouffard. 1982. Transcript. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston. Charleston, SC. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:23397. (accessed 10/8/2021).