» The Fraught Relationship between African Americans and Military Service by Mateo Mérida

Historically, patriotism has been intimately tied with acts of military service. Images of Uncle Sam, the raising of the flag on Iwo Jima, or even Captain America are seen not only as symbols of American military excellence, but as defining American patriotism itself. By consequence, the connection between the military and patriotism has been an imperative connection for marginalized people as a means of elevating the social standings of their communities, which is consistent for Black Americans as well.

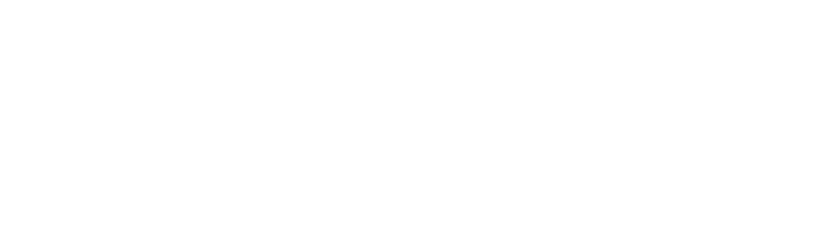

Avery Research Center: Walter Pantovic Slavery and African American History Collection. “African American Woman and Union Army Soldier.” 2014. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:80209

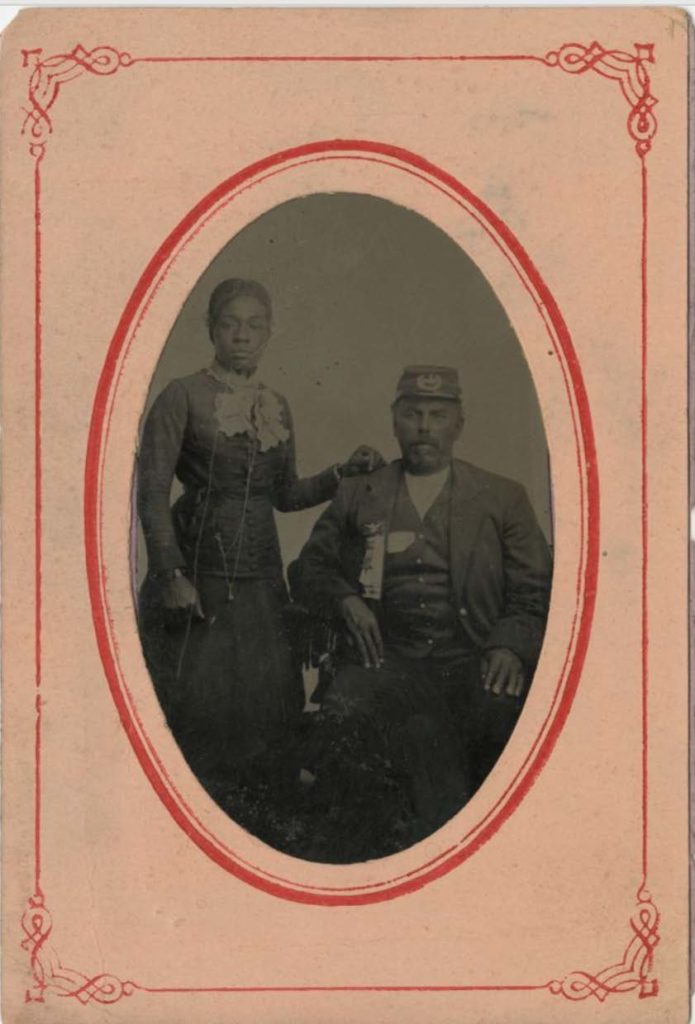

Avery Research Center: Walter Pantovic Slavery and African American History Collection. “Photo of an African American Man Posing Next to a Military Truck.” 2014. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:80162

While Black veteranship is visible as early as the American Revolution in both American and British ranks, the Civil War was pivotal in the history of Black Soldiers in North America. Frederick Douglass, a firm advocate for the recruitment of Black soldiers in the war said “Once let the Black man get his person the brass letter U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on the earth or under the earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship in the United States.”1 When Black soldiers were permitted to join the army, African American men enlisted in droves to actively eliminate slavery across the United States. For Black men like Douglass, it was believed that by joining the military, fighting for American values, and sacrificing their lives in the process, there could be no argument made that Black people born in the U.S. were not proud Americans and there could also be no argument strong enough to completely deny them citizenship.

Shortly after the end of the Civil War, the 13th and 14th Amendments banished slavery (except for those who committed a crime), and granted all African American people citizenship in the United States. While the passing of these Amendments was a major victory for Black civil rights in the United States, a full Civil Rights reform wouldn’t see any more meaningful change until the 1960’s. In the period between the Civil War and the civil rights movement, a military career did not uplift Black Americans in all of the ways they might have anticipated.

When Black veterans returned home to the United States, they had hoped that their veteran status would make them heroes in their communities. However, this was not the case. Violence was still a staple of Black oppression. In 1917, after returning home from service at the end of WWI, the Black veteran Charles Lewis returned to his home in Ohio. Roughly a month later, a strange man burst into Lewis’ home, accusing him of robbery, leading Lewis to run from his home, dressed in his old uniform. When he was apprehended by the white legal authorities, he was thrown in jail, and lynched the very next day.2 Other soldiers, such as the world renowned Buffalo Soldiers were so angered by being required to abide by the Jim Crow laws of Houston, Texas—despite their military status—that it led to a riot in August 1917.

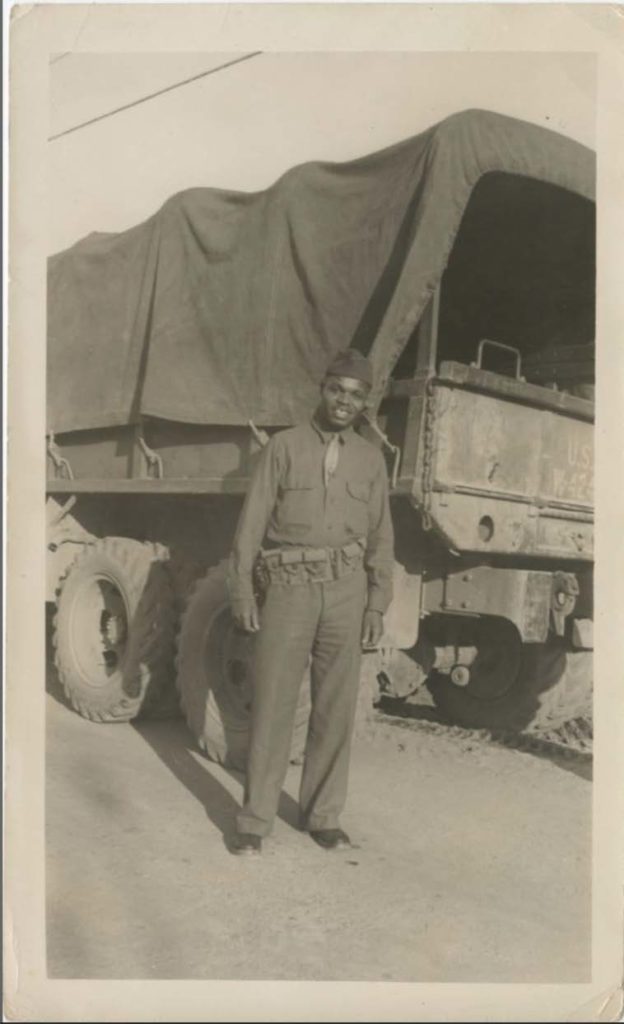

Despite their experiences immediately following the First World War, many Black veterans hoped for a substantial change in the domestic battle against racism and inequality after the United States became involved in World War II. The “Double V campaign” emerged during this period in reference to a victory against fascism abroad and a victory against racism in the United States. Still, no sweeping changes arrived for Black Americans domestically, even

where radical policies were created that superficially guaranteed a tangible impact in life at first glance.

Following WWII, the G.I. Bill enabled American veterans to pursue an advanced education with the knowledge that their finances were covered by the U.S. government. In theory, this policy also enabled Black veterans to attain a higher education themselves. However, Black veterans were met with a myriad of caveats that white veterans were not. For the majority of Black veterans who lived in the South, segregation prevented these potential students from advancing their education, leaving historically Black colleges and universities to turn many students away as a result of a lack of resources and the overwhelming number of applications they received. In Northern states, Black applicants were actively discriminated against in the admission process, while white veterans were admitted en masse. Policies like the G.I. Bill launched much of the white middle class into well paying positions as a result of their newly earned college degrees, while the families of Black veterans remained in poverty and in segregation, with little else to show for a military career.3

Frustrated by the lack of progress in the fight against racism at home, many Black WWII veterans sought to make the changes themselves. Organizers and activists like Medgar Evers, James E. Campbell, and Isaac Woodward and many other WWII veterans laid the groundwork for the civil rights movement using the discipline and training they received in the armed services to mobilize thousands in the struggle for Black liberation.

By the 1960’s, the view many African Americans previously held about military service as a tool for changing social conditions began to wane considerably. Some saw it as an active tool of oppression. In an essay written in the mid-20th century by activist and educator, Septima Clark, she declared: The contradiction between squandered wealth and dehumanizing poverty; the contradiction between a congenital racism and feeble efforts at becoming a democracy; the contradiction between a tradition of civilian controlled government, academic and other institutions on the one hand and the institutional power requirements of the military industrial complex on the other, all of these are exacerbated by the escalation of the power of the military on the affairs of the nation today.4

With the military being the primary driver of American affairs, according to Clark, it is then the chief reinforcer of all related social issues domestically and internationally in relation to the United States. Clark’s overarching view of the role of the military in the United States shows that the view of the military among Black Americans in the 1960’s was not a solitary fixed ideology. In contrast to the soldiers of the Civil War, World War I and II eras, many Black Americans in the Civil Rights Movement no longer saw the military as a legitimate tactic in the struggle for Black liberation.

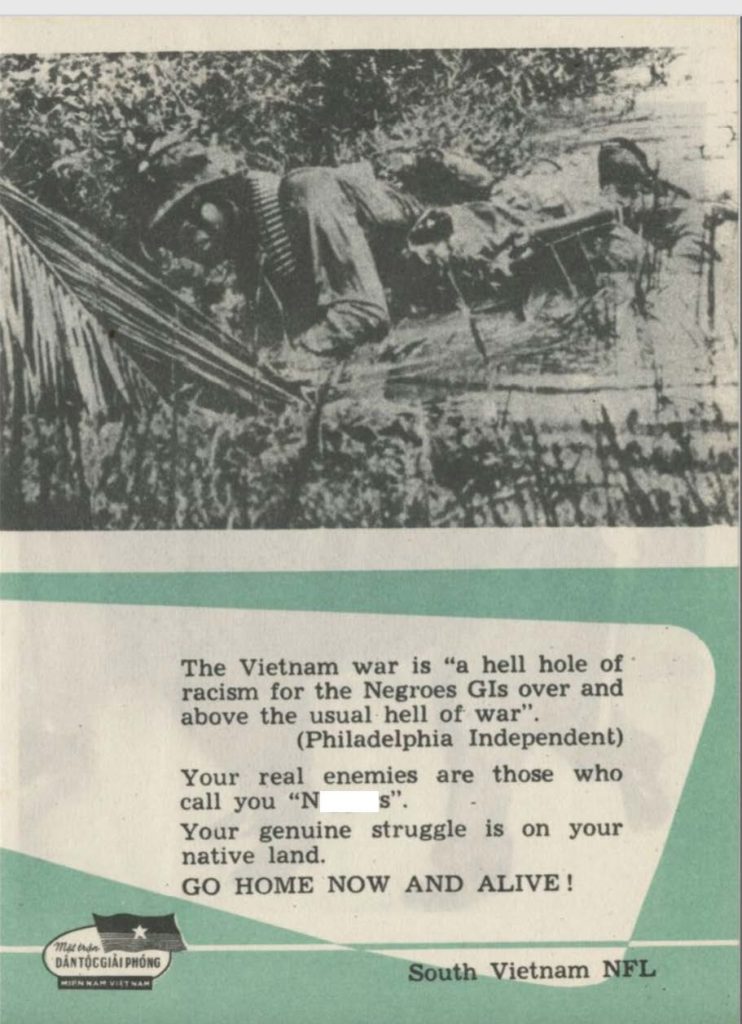

This view was not restricted inside the United States. The Vietnam War became the second longest war in American history, second only to the War in Afghanistan. To create a disruption within the American forces in Vietnam, the South Vietnam National Liberation Front created pamphlets geared towards Black soldiers fighting in Southeast Asia. “Your real enemies are those who call you ‘N*s’. Your genuine struggle is on your native land. GO HOME NOW AND ALIVE!”5

The legacy of African American soldiers in the military is one that is not easy to define. While the military has been an important mechanism for improving the lives of many Black American families, it has also been little overall to close the gaping disparities Black people face daily in the United States. The place that the military holds in Black American history is variable, and has been subject to change with the times and events of the day.

Citations

- Kelley, W. D, Anna E Dickinson, and Frederick Douglass. Address at a Meeting for the Promotion of Colored Enlistments, Philadelphia. July 6, 1863. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mfd.22007/.

- Williams, Chad. “African-American Veterans Hoped Their Service in World War I Would Secure Their Rights at Home. It Didn’t.” Time Magazine. November, 12, 2018. Accessed November 4th, 2021. https://time.com/5450336/african-american-veterans-wwi/.

- Herbold, Hilary. “Never a Level Playing Field: Blacks and the GI Bill.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. No. 6. Winter, 1994-1995. https://doi.org/10.2307/2962479.

- Clark, Septima Poinsette. Avery Research Center: Septima P. Clark Papers, ca. 1910-ca. 1990. “The New Resistance Movement.” 2016. Pp 2. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:92641.

- Avery Research Center: Walter Pantovic Slavery and African American History Collection. “Vietnam War Propaganda Card.” 2014. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:80152.